- Home

- Louis Zamperini

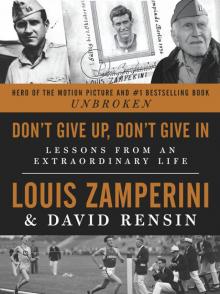

Don't Give Up, Don't Give In

Don't Give Up, Don't Give In Read online

Dedication

_______

FOR MY LATE WIFE, CYNTHIA;

MY CHILDREN, CISSY AND LUKE;

AND MY GRANDSON, CLAYTON

Contents

_______

Dedication

Epigraph

Coauthor’s Note

Introduction

RUN FOR YOUR LIFE

The Family Rules

Anyone Can Turn Their Life Around

The Difference Between Attention and Recognition Is Self-Esteem

It’s Not How You Win, It’s How You Lose

A Race Isn’t Over Until It’s Over

BE PREPARED

Preparation Determines Your Survival

My Survival Kit

Trust What You Know

Keep Your Mind Sharp

Don’t Forget to Laugh

DON’T GIVE UP, DON’T GIVE IN

You Are the Content of Your Character

Never Let Anyone Destroy Your Dignity

Hate Is a Personal Decision

The True Definition of Hero

ATTITUDE IS EVERYTHING

You Must Have Hope

Don’t Ask Why, Ask What’s Next

You Choose How to View Your Fate

The Secret of Contentment

AFTER THE WAR: STILL LOST

You Can’t Run (or Sail) Away from Yourself

Don’t Leave the Crucial Details to Others

THERE’S ALWAYS AN ANSWER TO EVERYTHING

You Need a Cloud to Have a Silver Lining

Know When You’ve Done All You Can Do

The Gangster and the Gospel

GIVE BACK

It Takes a Camp to Help a Child

Get Their Attention

First You Listen

Accomplishment Is the Key to Self-Respect

My Private Reward

The Mission That Never Ends

WHAT I’VE LEARNED

Challenge Yourself

Learn to Adapt

Commitment and Perseverance Pay Off

You’re Only as Old as You Feel

Free Advice

LESSONS OF THE OLYMPIC SPIRIT

It’s About People

You Have to Train to Carry a Torch

Forgiveness Is the Healing Factor

REMEMBER ME THIS WAY

A Charitable Heart

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Books by Louis Zamperini

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Epigraph

_______

People tell me, “You’re such an optimist.” Am I an optimist? An optimist says the glass is half full. A pessimist says the glass is half empty. A survivalist is practical. He says, “Call it what you want, but just fill the glass.”

I believe in filling the glass.

—LOUIS SILVIE ZAMPERINI

Coauthor’s Note

_______

When I learned that Louie Zamperini had died on July 2, 2014, I didn’t want to believe that he was gone. Impossible. Inconceivable. Just two days earlier we had sent the manuscript for this book to our editors, and I looked forward to us celebrating its publication. But sadly, death comes for us all—even for those like Louie who deserve to live forever.

Louie’s family issued this statement: “After a forty-day-long battle for his life, he peacefully passed away in the presence of his entire family, leaving behind a legacy that has touched so many lives. His indomitable courage and fighting spirit were never more apparent than in these last days.”

“We’re all a little afraid of death,” Louie had said the last time we’d met, when we broached the subject of mortality. “We’re afraid because no matter how old you are you’re always making plans and you don’t want to be interrupted. I’m ninety-seven years old, but after everything that’s happened in my life, I feel as if I’ve lived two hundred years—and I wouldn’t mind two hundred more so that I can keep doing what I’ve been doing.”

What he’d been doing, he explained, was “helping the underdog. That’s been my program. That’s been my whole life.”

SINCE COLLABORATING WITH Louie on his 2003 autobiography, Devil at My Heels, we’d become friends. When we spoke—or had a meal when he had the time; Louie was always going somewhere, doing something (age did not seem to affect him)—he would talk nonstop, regaling me with stories of his latest adventures, travels, and appearances. I’d hear about celebrities he’d met (who were as impressed with him as he was with them), fan letters he’d received, people he’d helped, and impromptu tales from his life after the war. He’d tell me about Unbroken author Laura Hillenbrand’s latest research discovery. He’d ask about my wife and son, give parenting advice, and talk proudly about his family.

Every now and then my phone would ring and there would be Louie, who, without much preamble, would launch into new thoughts for this book while I scrambled to turn on the tape recorder. We’d begun sketching out Don’t Give Up, Don’t Give In after Devil at My Heels was published. At the time, it was called All Things Work Together for Good, which was a bedrock aspect of Louie’s attitude toward life. But Unbroken had come along, and with it in the works Louie really had no time to spare, so we decided to put our next project on the back burner. In the meantime, because he’d occasionally kvetch about how busy he was, I loved to tease him about what I promised would be the reaction to Unbroken, and all the attention he’d get. “If you think you’re busy now, just wait,” I told a man who had already been a huge public figure for most of his life.

In December 2013, Louie’s daughter, Cynthia, called with some news. “My dad says he still has stories he wants to tell.” Was I interested in reviving our book?

I immediately said yes. I cleared my schedule and we met weekly to work on what we now titled, Don’t Give Up, Don’t Give In. Unlike our first collaboration, our sessions couldn’t go on for hours. Louie was, after all, ninety-seven. But age had not diminished his always unflagging enthusiasm. And his mind was clear. So we sat in his home office, looking at the broad sweep of Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles through the picture window, he wearing his University of Southern California cap and blue jacket, and me pushing the digital recorder closer and closer to make sure I got every word.

Once, when I arrived for our usual 10 a.m. appointment, Louie answered the door.

“Oh, no!” he said. “It’s you.” This was not his usual greeting. I discovered I had been mistakenly left off the schedule.

“Are you okay?” I said. He looked a bit worn out.

“I just woke up,” he said. “Tom Brokaw was here yesterday interviewing me, and they had to put cardboard all over the floor for the equipment, and there were so many people, and … I’m a little exhausted.”

“Let’s just reschedule,” I said.

“No, no. Come on in. I can talk for half an hour, okay?”

Typical Louie, he got more loquacious as he reminisced with relish about both a sailing trip along the Mexican Baja coast during which he’d gone missing and a pesky parrot named Hogan. He loved Hogan. “Make sure Hogan is in the book,” he reminded me, when I finally said goodbye an hour and a half later.

Of course, this book wasn’t Louie’s only project. Unbroken had become a film, directed by Angelina Jolie, and he’d promised to be available to help however he could to support and promote it. And then there was his daily life: meals with the family, reading the never-ending fan mail and requests for photos and autographs, figuring out ways to help kids in need (a habit for sixty-five years), and looking forward to when Angelina would come to visit, often bearing gifts.

“He was m

y friend, my mentor, my hero,” she said after Louie’s passing, “It is a loss impossible to describe. We are all so grateful for how enriched our lives are for having known him. We will miss him terribly.”

Like so many others, I cherished my time with Louie. I marveled at his cheerfulness, open heart, self-awareness, and stunning ability to forgive. He was the content of his character and an example to us all. And yet, I know that I am not alone in finding it almost impossible to explain Louie’s essence, to articulate exactly what made Louie who he was. Why was he so special? Did he even know? The answer now remains just out of reach.

In the end I guess that’s how it should be, leaving us all the more about which to ponder and reflect, and to miss about him always.

—DAVID RENSIN, JULY 2014

Introduction

_______

F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote that “there are no second acts in American lives.”

I don’t believe that. How could I?

I’m ninety-seven and I’ve done and been through so much that I feel as if I’ve lived for two hundred years. My mind is still sharp, my spirit is full, and I haven’t lost my zest for life.

Some of you know my story because you’ve read my 2003 autobiography, Devil at My Heels. Or you’ve read about me in Laura Hillenbrand’s 2010 bestselling biography, Unbroken, which has become a movie directed by Angelina Jolie. Maybe you were in the audience when I spoke at your school, church, hospital, or organization. Perhaps you saw me run with an Olympic torch, or watched me being interviewed on television, or discovered my war exploits in a magazine or newspaper. Did you spend a week at my Victory Boys Camp? I’ve given talks on cruise ships, and to the military. Did I counsel you or a member of your family when the need arose, or just be seated at the table next to yours at El Cholo, my favorite Mexican restaurant in Los Angeles?

I’ve done a lot, so anything is possible.

As a kid growing up in Torrance, California, in the 1920s and 1930s, I made more than my share of trouble for my parents and the neighborhood, and mostly got away with it. But at 15, thanks to my older brother, Pete, I turned my life around. Just in the nick of time he showed me how to channel my skill for running away from the police into a talent for racing around a high school track—and after a brief rough start, I took to it as if I’d been thrown a life preserver. In 1934, when I was 17, I set the high school interscholastic world record for the mile of 4:21.2, at the prelims for the California State Championships.

After graduating from high school in 1936, I made the U.S. Olympic team for the 5000-meter race by running to a dead heat for first place with Don Lash in the trials. I only placed eighth in Berlin against other great runners—Lash came in 13th—but I was the first of my team across the finish line. Hitler noticed my 56-second final lap and asked to meet me. “Ah, you’re the boy with the fast finish,” he said. And that was that.

I attended the University of Southern California between 1936 and 1940, and ran with a passion. I set the National Collegiate Athletic Association mile record in 1938 at the championship meet in Minneapolis. My time of 4:08.3 stood for fifteen years. In 1939, I ran a few seconds slower, but won the mile race again. My goal was to be the first to break the four-minute mile barrier at the 1940 Tokyo Olympics, and the consensus was that I had an excellent chance. But World War II got in the way. I was heartbroken.

I got a job at Lockheed Corporation in Burbank. During lunch, I’d watch one P-38 after another fly in and out of the company airfield. That seemed exciting so I applied to the Army Air Corps to be a pilot, but washed out of flight school because I couldn’t take spinning in the air. Instead I became a bombardier, stationed in Hawaii. I flew in many hair-raising raids throughout the Pacific theater, including narrowly escaping death when our B-24 bomber, nicknamed Superman, was all shot up in a raid on the island of Nauru.

On May 27, 1943, while on a rescue mission near Palmyra Atoll, eight hundred miles south of the Hawaiian Islands, the beaten-up B-24 we had to use at the last minute—it no longer flew combat missions—blew an engine as we scanned the ocean at eight hundred feet. We crashed into the Pacific. I was trapped in the fuselage and going down. I thought I was a goner.

Miraculously, I survived. When I surfaced I saw that the pilot, Phil (Russell Phillips), and tail gunner, Mac (Francis McNamara), were alive too. The ocean was on fire and our other eight crewmen were gone. I managed to snag two life rafts, gave Phil first aid for a serious head gash, and then settled in to wait for our boys to find us.

No one did.

The tail gunner panicked the first night and ate all the enriched chocolate rations while Phil and I slept. Now we had nothing. Days passed. We survived on the occasional—raw—albatross that landed on the raft and the few fish that the sharks didn’t get first, and caught a couple of small sharks and feasted on their livers. We had little protection from the sun and, after our limited water ration ran out, fresh water only when it rained. But we did have one advantage: our minds. Thanks to the mental discipline I’d developed as a world-class athlete, and the wisdom I’d absorbed from a wise physiology professor at USC, I was able to keep sharp and help Phil do the same.

On the twenty-seventh day we saw a plane. Rescue? No, a Japanese fighter. It strafed us again and again. We slipped into the water to avoid the bullets, and kept an eye out for sharks—and a fist ready to punch their snouts if they came too close. We escaped injury but the rafts were riddled with holes and needed serious pumping and patching while the sharks circled. Then a great white shark began to hunt us.

After thirty-three days Mac died. We buried him at sea. Phil and I hung on.

By then I had begun to do what everyone in a real or metaphorical foxhole does: I desperately asked God to intervene, saying, “I promise to seek you and serve you if you just let me live.”

By the forty-sixth day we’d drifted nearly two thousand miles west to the Marshall Islands. After surviving a huge storm, we were rescued on the forty-seventh day—emaciated and near death—by the Japanese.

Initially they were decent, but that quickly devolved into two and a half years of torture and humiliation at numerous prison camps, much of it doled out by Sergeant Mutsuhiro Watanabe, a psychopathic and vindictive prison guard nicknamed the Bird. He thought that if he beat me enough I’d make propaganda broadcasts for the Japanese. I never did.

When the war ended, Phil and I were still alive and made it home. The press called me a hero. To me, heroes are guys with missing arms or legs—or lives—and the families they’ve left behind. There were so many. But because I was an Olympian and a sports celebrity with an incredible story—including having been declared dead by the Army—I got lots of attention. I can’t say I didn’t like it.

What I didn’t like was that I couldn’t find my place in the world and had what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). To compensate for growing frustration and a desire to take revenge for the misery I’d been through, I drank too much, got into fights, had an inflated ego, and no self-esteem. I also had constant nightmares about killing the Bird.

Somehow I managed to hold it together enough to meet and marry the girl of my dreams, Cynthia Applewhite. But I was caught in a relentless personal downward spiral, and almost lost her, my family, and my friends before I hit bottom, looked up—literally and figuratively—and found faith in 1949, in a tent on a Los Angeles street corner, listening to a young preacher named Billy Graham. The drink went down the drain. No more smoking. No more fighting. And I never dreamed of the Bird again.

But deciding to devote your life to God, whatever your religion, doesn’t mean instantaneous, nonstop happiness. Hard work lay ahead. I fought despondency and doubt, and tried to come to terms with what had happened to me after years of taking life for granted.

My faith grew. A year later I returned to Japan. I asked to meet my prison guards—now incarcerated as war criminals—determined to forgive them all in person. The hardest thing in life is to forgive. But hate is self-d

estructive. If you hate somebody you’re not hurting the person you hate, you’re hurting yourself. Forgiveness is healing.

I wanted to forgive the Bird, too, but he was listed as missing, possibly a suicide.

When I returned home, I remembered the promise I’d made on the raft. I’d finally sought Him. Now I was determined to serve Him—and I did. For more than sixty-five years, I’ve devoted myself to a life of service and of sharing my story.

I have never ceased to be amazed at the response.

I’M OFTEN ASKED if, given the chance, I’d live my life the same way again. I have wondered about that as well—for about five seconds. When I think of the juvenile delinquency, injuries, torture, and many near-death experiences, the answer is a definite no. That would be crazy.

Of course, enduring and surviving those challenges led to many years of positive influence which helped neutralize the catastrophes and eventually delivered great rewards. I’ve been honored and blessed with impossible adventures and opportunities, a wonderful family, friends, and fans all over the world. That I’d gladly repeat.

It’s obvious that one part of the story can’t happen without the other.

And so I accept it. I am content.

YOU’D THINK THAT all that’s happened to me would be plenty for one life, but unlike General MacArthur, this old soldier would not simply fade away.

In 1956, a publisher asked me to write an autobiography. I called it Devil at My Heels. We did it quickly and I wasn’t crazy about it, but Universal Pictures bought the rights for Tony Curtis to play me. He made Spartacus instead, and my movie never happened. I didn’t mind.

At the same time, I started an outreach camp program for boys who were as wayward as—or worse than—I had been. Victory Boys Camp was Outward Bound before Outward Bound. Thousands of boys got the counseling and fresh start they needed, and I would eventually help establish similar programs in England, Germany, and Australia.

Don't Give Up, Don't Give In

Don't Give Up, Don't Give In